dinki

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

WE ALWAYS RUN

We always run away, from town to town,

we- intellectuals:

small and shivering, a tribe without a tribe,

a class of ineffectuals.

From country to country, we shift about with our families:

we each have a gramophone,

millions of us. But it's no use. They keep asking:

"Which country is your own ? "

And since we don't know, we can only weep

oceans of salt oblations.

Beneath fake palms we write artificial letters

and post them in dirty stations.

Translated by Jerzy Peterkiewicz and Burns Singer

Source: www.ap.krakow.pl

This poem needs little explanation. It is one of the many famous poems by Gałczyński about a black period in his life. The poet's absolute love for, and faith in, his wife Natalia are as much the bedrock of this poem as is the hopeful and listless mind of the poet.

Letter From a POW

My dearest, my heart-call,

Goodnight my love-you are tired,

I see your shadow on the wall.

The night is so Spring inspired.

You are my all in this world,

How to make famous your name?

You're my water in Summer,

My gloves in Winter's bane.

You are my good fortune, Vernal

Summery, Wintry and Autumnal.

So call to me goodnight,

Whisper it through your sleepy mouth.

But what is the payment for this sight,

The blissful paradise by your side.

In my world you are the light,

The songs of my road that will guide.

Introduction and translation by Barry Keane

Source: Warsaw Voice

Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński (January 23, 1905 - December 6, 1953) was a Polish poet.

Born in Warsaw, he moved to Moscow at an early age and upon returning to Poland studied classical and English language at the University of Warsaw.

He debuted in 1923 and was a member of the Kwadryga group of poets. In 1930, he married Natalia Avalov.

Mobilised during the Polish September Campaign, he spent most of the war as a prisoner of war. Returning to Poland in 1946, he was a contributor to the Przekrój and Tygodnik Powszechny magazines, among others. However, many of his post-war poems, including a vituperative diatribe against Czesław Miłosz, are largely ignored as supportive of the Communist regime.

Among his most known works are the satirical mini-pieces of "Teatrzyk Zielona Gęś" ("Green Goose Theatre").

He married Lucile Wolanowska in the 1940s and had a son on 22 January 1946.

Source: Wikipedia

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

The Man You Love to Hate

8 December 2004

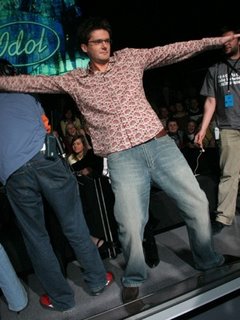

“I like being disliked,” he told the Voice. Who is this Polish journalist, showman, talk-show host and controversial judge of last year’s international edition of Pop Idol?

■ Agent provocateur

“My family in the United States is deeply convinced that I am like David Beckham combined with the Spice Girls in Poland, since I am on the front-page or the centerfold in every other issue of every Polish tabloid,” jokes Kuba Wojewódzki. Journalists and Internauts have described him as: “total zero,” “jerk,” “serial idiot,” “rampant cynic,” and “artificial creation of commercialism.” Positive reactions to Wojewódzki hail him as “the best,” “the coolest guy on TV,” “a unique personality,” “star” and “the master of irony.” Last December, the world watched American critic Simon Cowell call Wojewódzki a moron during the final competition of the international edition of Pop Idol. Vocalist Krzysztof Cugowski, leader of rock band Budka Suflera, calls him a “simpleton.”

“I want to live according to the biography I would write myself,” Wojewódzki once said. Now aged 41, he achieved widespread fame and popularity only three years ago as the ruthless jury member of Poland’s first edition of Pop Idol. During the program Wojewódzki littered his comments with quotations and was erudite—with a sharp and controversial wit. One contestant was told that if walls could commit suicide, they would have done it after hearing his singing. On another occasion, he compared one female participant to a hooker.

Wojewódzki never ceases to surprise. “I am nobody,” he wrote on his homepage. At the same time, he considers himself a TV personality. Asked about the most controversial figure in Poland, most Poles point to Wojewódzki—tall, slim and wearing his trademark glasses. “People and the media have worn out the words scandalous and controversial,” Wojewódzki said. “To me, Osama bin Laden is a controversial figure. George W. Bush is another: he gets things confused and his scandals are not always intentional.” Wojewódzki believes scandal is not an end in itself. “My aim is to make people think,” he said. “When I piss somebody off, I also force them to take a stance. Indifference is the worst position.”

“I think his denials of being a controversial figure are justified,” said sociologist Dr. Mirosław Pęczak. “He is in no way such a figure, but he does his best to be a prominent figure in the media.” Asked why reactions to Wojewódzki are always extreme, Pęczak says: “That’s the whole point.”

■ Idol child

Wojewódzki is quite right to call himself a child of Idol. “I was 38 when the program started,” he said. Despite his previous achievements (see box), it was only then that people noticed and appreciated him. “Mass popularity came at the right moment,” Wojewódzki believes. “I don’t feel anointed. I am a normal, average person who has become popular as a result of luck.” Wojewódzki was always the most notable Idol jury member. He says no one is allowed to interfere with his TV appearances, everything is his own creation. Sociologist Pęczak has a different view: “I believe his role was artificial. The Pop Idol format calls for a bad guy, who just happened to be Wojewódzki.”

It was no coincidence that Wojewódzki was sent to London in December 2003 to sit on the international jury. “Nobody has ever embarrassed Poland internationally the way Kuba Wojewódzki did,” an Internaut wrote afterwards. Viewers remembered him as the guy who only spoke Polish and turned each of his statements into a small-scale show. Wearing the famous Samoobrona tie and brandishing a bottle of Polish vodka, he ridiculed and scoffed at everything and everyone. A year later, he says the event was a complete bore: “World Idol was of a similar standard as the Eurovision Song Contest. I am glad I told Kurt Nielsen he was the only real artist—and he won. I was embarrassed about the whole show. The entire jury was offended, but that only proves I was noticed. The problem was that other figures were supposed to steal the show. Then all of a sudden someone else rocked the boat.”

Soon after, Wojewódzki was approached with proposals to take part in other programs. “They wanted to solve the puzzle of that weird, skinny idiot from Poland. I didn’t go anywhere, not even to Denmark.” With brutal honesty, Wojewódzki admits he didn’t feel like going: “That was just one episode for me. I could have gone there for 3,000 kroner and a hotel room, but what would be the point? Am I supposed to explain why I didn’t like it?” He has no regrets about his performance, which he considers an amusing experience. Not everyone shares his opinion. Wojewódzki admits that during a trip to Egypt with his girlfriend for New Year’s Eve, he was recognized by a group of German tourists. They sat frozen and didn’t know how to behave. After the Pop Idol finals, a number of articles about Poland’s offensive judge were published in international press. Some titles, especially those in the British press, were often harsh. “They have invited me to another edition,” Wojewódzki revealed. “They want high ratings. If I can ruin Christmas for a few Europeans, then maybe I will take the plunge?” he sneers. “I know I may have acted improperly, for which I apologize to the entire European Community. This time they might cut off my mike to sabotage me.”

■ Talk show evolution

Wojewódzki says his most satisfying accomplishments are in radio and TV. “I don’t have any plans, I am just living my dream,” he said. “When I get tired, I’ll quit.” Wojewódzki’s eponymous talk show is celebrating its second anniversary. Each Sunday evening, it attracts 2-3 million viewers. “I run the program partly as a serious venture and partly as a joke,” Wojewódzki said. Sometimes he offends and disgusts guests, but always provokes their reactions in difficult, uncomfortable situations. Wojewódzki does his best to demonstrate that he doesn’t acknowledge any subject as taboo. That is why many guests, for example controversial Ich Troje vocalist Michał Wiśniewski, refuse to appear. “Some have a different sense of humor and esthetics,” Wojewódzki explains in reference to Wiśniewski. “Actor Paweł Wilczak says he will accept my invitation once I start listening to my guests. But I do!”

“The talk show seems designed to present an image that is either non-existent or extremely rare in Polish media,” said Pęczak. “This is a one-man show, a format frequently used on German and American channels, a Polish counterpart to the Jerry Springer’s show.” The sociologist says he has observed a certain evolution during the course of Wojewódzki’s talk show: “Programs are more frequently focused on an actual conversation rather than an attempt to show off.” The latter is a common grudge against Wojewódzki. “We are dealing with a recognizable TV personality who wants his guests to distinguish themselves on his show,” Pęczak says.

Wojewódzki causes a sensation everywhere he goes but according to the host himself, people react quite positively. “At first, it was a shock, I was perceived as a jerk, but now people begin to understand I am making a show, that this is all tongue in cheek. There are no groupies hanging around my door, so I’ll survive.” Still, during the recent film festival in Kazimierz Dolny, he had to escape or be trampled by the crowd. “It doesn’t matter who you really are, [for some] you will always be the guy on TV,” he says with sarcasm. “They want a photo and treat you like a pet.” Given his notoriety, it is surprising that Wojewódzki hasn’t appeared in a commercial yet. “I got lots of proposals right away, including one from a big foreign brewery. The commercial would have been shot in Mexico, but they told me I was meant to be a ‘recognizable Polish element and not in the foreground.’ I said: no.”

Wojewódzki says he has so much fun on his talk show that he considers it to be a social event. “He plays a sort of game in which both he and the viewers are tokens,” Pęczak said. “He constantly provokes, but in my opinion, he never crosses the line in terms of decency. Still, he doesn’t always convince me that what he says is not just an act.”

Wojewódzki says he only watches his program during the editing phase and never on TV. “I am not a narcissist who watches himself and says: what a great punchline, wow!” He add quickly: “I’m so in love with myself already that I’m afraid I wouldn’t have anything to criticize...”

Resumé

Kuba Wojewódzki, age 41, journalist; favorite books: Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and The Devil by Alfonso di Nola; former publisher and editor-in-chief of Brum and Plastik magazines; creator of music videos; recorded an album with a band called Indios Bravos; former director of the alternative music festival in Jarocin; car afficionado.

Source: The Warsaw Voice

Monday, August 28, 2006

MANUELA GRETKOWSKA

A novelist, she was born in Lodz in 1964. She graduated from the Jagiellonian University in Cracow with a degree in philosophy and went to Paris in 1988 to study medieval anthropology at the École des Hautes Études Sociales in Paris. She published her first novel, WE ARE RUSSIAN EMIGRÉS, in 1990. That and her next three books deal with Paris and the loves of a protagonist quite similar to Gretkowska herself; the barely-sketched plot is interwoven with essays of a historical-literary or popular scientific nature, reportage, ironic commentaries, the grotesque, and heretical religious treatises. Although her first book contains echoes of political protest, Gretkowska was never a political emigré. She is rather a citizen of the world who can live and work anywhere. She returned to Poland in the early 1990s to work on the staff of the local version of Elle, before leaving for Sweden, where she now lives, in 1997.

Gretkowska's books are bestsellers, evoking extensive comment and heated emotions. Her prose, variously described as post-modernist, feminist, metaphysical, or scandal-mongering, has won a broad and varied readership. Her book, WORLD WATCHER, appeared in 1998, is a collection of reportage from various countries, highly personal and full of digressions as always, some of which had previously been published in Elle.

Source: www.polska2000.pl

Copyright: Stowarzyszenie Willa Decjusza

Selected Bibliography:

MY ZDIES EMIGRANTY / WE ARE RUSSIAN EMIGRÉS, Warsaw: W.A.B., 1990

TAROT PARYSKI / THE PARISIAN TAROT, Cracow: Oficyna literacka, 1993

KABARET METAFIZYCZNY / METAPHYSICAL CABARET, Warsaw: W.A.B., 1994

PODRECZNIK DO LUDZI / A TEXTBOOK ON PEOPLE, Warsaw: Beba Mazeppo & Co., 1996

SWIATOWIDZ / WORLD WATCHER, Warsaw: W.A.B., 1998

NAMIETNIK / THE PASSIONARY, Warsaw: W.A.B, 1998

SILIKON, Warsaw: W.A.B, 2000

POLKA, Warsaw: W.A.B, 2001 more...

SCENY Z ZYCIA POZAMALZENSKIEGO / SCENES FROM OUT OF A MARRIAGE (with Piotr Pietucha), Warszawa: W.A.B., 2003

Selected translations:

French: LE TAROT DE PARIS, Paris: Flammarion, 1996